Just Prior to the first arrival of Europeans in 1778, the inhabitants of the Hawaiian Islands lived in a highly organized, self-sufficient, social system, with a sophisticated language, culture, religion and a land tenure that bore a remarkable resemblance to the feudal system of ancient Europe.

The monarchical government of the Hawaiian Islands was established in 1810 by His Majesty King Kamehameha I (pictured right). He ruled the Hawaiian Islands from April 1810 until his death in May 1819. Upon the death of King Kamehameha I, his son King Kamehameha II was successor to the throne and ruled the Hawaiian Islands from May 8, 1819 to July 1824 when he died of measles in London. His Majesty King Kamehameha III, the second son of His Majesty King Kamehameha I, was successor to the throne upon the death of Kamehameha II in July 1824.

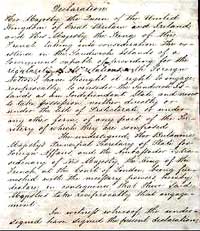

The Hawaiian Kingdom was governed until 1838, without legal enactments, and was based upon a system of common law, which consisted partly of the ancient kapu (taboo) and the practices of the celebrated Chiefs, that had been passed down by tradition since time immemorial. The Declaration of Rights, proposed and signed by His Majesty King Kamehameha III on June 7, 1839, was the first essential departure from the ancient ways.

Establishing a Constitutional form of Government

for the Hawaiian Kingdom (circa. 1839).

The Declaration of Rights of 1839 recognized three classes of persons having vested rights in the lands; 1st, the Government; 2nd, the Chiefs; and 3rd, the native Tenants. It declared protection of these rights to both the Chiefly and native Tenant classes. These rights were not limited to the land, but included the right to ". life, limb, liberty, freedom from oppression; the earnings of his hands and the productions of his mind, not however to those who act in violation of the laws."

One year later on October 8, 1840, His Majesty King Kamehameha III (pictured left) voluntarily relinquished his absolute powers and attributes, by promulgating a constitution that recognized three grand divisions of a civilized monarchy; the King as the Chief Executive, the Legislature, and the Judiciary. The Legislative Department of the Kingdom was composed of the King, the House of Nobles, and the House of Representatives, each had a negative on the other. The King represented the vested right of the Government class, the House of Nobles represented the vested right of the Chiefly class, and the House of Representatives represented the vested rights of the Tenant class. The Government was established to protect and acknowledge the rights already declared by the 1839 Declaration of Rights.

The Constitution generally defined the duties of each branch of government. Civilly, the laws embraced the usual rights and duties of the social relations between the three classes of people, and initiated the internal development of the country with the promotion of industry and commerce. In these laws, the fundamental basis of landed tenure was declared, and cultivation of the soil, under a feudal tenancy not much differing that of ancient Europe, was encouraged by relaxing the vassal service of the Chiefly and Tenant classes.

Hawaiian Kingdom recognized as an Independent State in 1843.

To counter the strong possibility of foreign encroachment on Hawaiian territory, His Majesty King Kamehameha III dispatched a Hawaiian delegation to the United States and Europe with the power to settle difficulties with other nations, and negotiate treaties. This delegation's ultimate duty was to secure the recognition of Hawaiian Independence from the major powers of the world. In accordance with this goal, Timoteo Ha`alilio, William Richards and Sir George Simpson were commissioned as joint Ministers Plenipotentiary on April 8, 1842. Sir George Simpson, shortly thereafter, left for England, via Alaska and Siberia, while Mr. Ha`alilio and Mr. Richards departed for the United States, via Mexico, on July 8, 1842.

On December 19, 1842, the Hawaiian delegation, while in the United States of America, secured the assurance of United States President Tyler that the United States would recognize Hawaiian independence. The delegation then proceeded to meet their colleague, Sir George Simpson, in Europe and together they secured formal recognition from Great Britain and France. On April 1, 1843, Lord Aberdeen on behalf of Her Britannic Majesty Queen Victoria, assured the Hawaiian delegation that, "Her Majesty's Government was willing and had determined to recognize the independence of the Sandwich Islands under their present sovereign."

On November 28, 1843, at the Court of London, the British and French Governments entered into a formal agreement for the recognition of Hawaiian independence. The Proclamation read as follows:

"Her Majesty the Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and His Majesty the King of the French, taking into consideration the existence in the Sandwich Islands of a government capable of providing for the regularity of its relations with foreign nations, have thought it right to engage, reciprocally, to consider the Sandwich Islands as an Independent State, and never to take possession, neither directly or under the title of Protectorate, or under any other form, of any part of the territory of which they are composed.

The undersigned, Her Majesty's Principal Secretary of State of Foreign Affairs, and the Ambassador Extraordinary of His Majesty the King of the French, at the Court of London, being furnished with the necessary powers, hereby declare, in consequence, that their said Majesties take reciprocally that engagement."

As a result of the recognition of Hawaiian Independence in 1843 the Hawaiian Kingdom entered into Treaties and Conventions with the nations of Austria, Belgium, Bremen (presently Germany), Denmark, France, Germany, Hamburg (presently Germany), Italy, Hong Kong (former colony of England), Japan, Netherlands, New South Wales (former colony of England), Portugal, Russia, Samoa, the Swiss Confederation, Sweden, Norway, Tahiti (colony of France), United Kingdom, and the United States of America.

The Organic and Statutory Laws of the State (circa. 1845-1886).

On June 24, 1845, a Joint Resolution was enacted by the Legislature and signed into law. The Attorney General was called upon to draw up a complete set of the existing laws embracing the organic forms of the different departments, namely, the Executive and Judicial branches. These laws were to outline their duties and modes of procedure. This brought forth the First Act of Kamehameha III to Organize the Executive Ministries, the Second Act of Kamehameha III to Organize the Executive Departments, and the Third Act of Kamehameha III to Organize the Judiciary Department. These Acts came to be known as the Organic Acts of 1845-46.

On September 27, 1847, the Legislature passed a law calling upon Chief Justice William L. Lee to establish a Penal Code. In 1850, a Penal Code was submitted to the Legislature by Chief Justice Lee and signed into law by His Majesty King Kamehameha III. The Penal Code had adopted the principles of the English common law. On June 22, 1865, the Judges of the Supreme Court were directed, by an act of the Legislature, to compile and ready to publish the Penal Laws of the Kingdom. The matter required a compilation of the amendments and additions made to the Penal Code since 1850. In 1869 a revised Penal Code was published.

In 1851, the Hawaiian Kingdom Legislature passed a resolution calling for the appointment of three commissioners, one to be chosen by the King, one by the House of Nobles, and one by the House of Representatives. The duty of these commissioners was to revise the Constitution of 1840. The draft of the revised Constitution was submitted to the Legislature and approved by both the House of Nobles and the House of Representatives and signed into law by the King on June 14, 1852. By its terms, the Constitution would not take effect until December 6, 1852.

On April 6, 1853, Alexander Liholiho was named successor to the office of the Constitutional Monarch by His Majesty King Kamehameha III in accordance with Article 25 of the Constitution of 1852. Article 25 provides that the ". successor (of the Throne) shall be the person whom the King and the House of Nobles shall appoint and publicly proclaim as such, during the King's life. "

One year later on December 15th, His Majesty King Kamehameha III passed away and Alexander Liholiho ascended to the office of Constitutional Monarch. He was thereafter called King Kamehameha IV (pictured right).

Since the passage of the Organic Acts of 1845-46, a Joint Resolution was passed by the Legislature and signed into law in 1856, calling upon Prince Lot Kamehameha, Chief Justice William L. Lee, and Associate Justice George M. Robertson to form a committee and prepare a complete Civil Code and to report the same for the sanction of the Legislature in 1858. Pursuant to the resolution, on May 2, 1859, a Civil Code was finally passed by the Legislative Assembly and signed into law on May 17, 1859. Session laws subsequently enacted by the Legislature amended or added to the Civil and Penal Codes.

The nationality or political status of persons ancillary to the Hawaiian Kingdom are termed Hawaiian subjects. The native inhabitants of the Hawaiian Islands became subjects of the Kingdom as a consequence of the unification of the islands by His Majesty King Kamehameha I at the turn of the 19th century. Since Hawai'i became constitutional, foreigners were capable of becoming Hawaiian nationals either through naturalization or denization. Under the naturalization laws of the Kingdom, foreigners who resided in the Hawaiian Islands for at least five years could apply to the Minister of Interior for naturalization, whereby "Every foreigner so naturalized, shall be deemed to all intents and purposes a native of the Hawaiian Islands, be amenable only to the laws of this Kingdom, and to the authority and control thereof, be entitled to the protection of said laws, and be no longer amenable to his native sovereign while residing in this Kingdom, nor entitled to resort to his native country for protection or intervention. He shall be amenable, for every such resort, to the pains and penalties annexed to rebellion by the Criminal Code. And every foreigner so naturalized, shall be entitled to all the rights, privileges and immunities of an Hawaiian subject."

Denization was a constitutional prerogative of the Office of the Monarch, whereby, a foreigner may have all the rights and privileges of a Hawaiian subject, but is not required to relinquish his allegiance to his native country as is required under naturalization. Denization was "dual citizenship," which was accompanied by an oath of allegiance to the Hawaiian Kingdom. It was reserved to those foreigners who may not have resided in the Kingdom for five years or more, but their services were necessary in the affairs of government both local and abroad. The children of Hawaiian denizens born on Hawaiian territory were considered Hawaiian subjects. Examples of Hawaiian denizens were special envoys who negotiated international treaties and officers serving in the Hawaiian government.

On November 30, 1863, His Majesty King Kamehameha IV passed away unexpectedly, and consequently, left the Kingdom without a publicly proclaimed successor. On the very same day, the Kuhina Nui (Premier) in Privy Council publicly proclaimed Lot Kapuaiwa the successor to the Throne, in accordance with Article 25 of the Constitution of 1852. He was thereafter called King Kamehameha V. Article 47, of the Constitution of 1852, provides that ". whenever the throne shall become vacant by reason of the King's death the Kuhina Nui (Premier) shall perform all the duties incumbent on the King, and shall have and exercise all the powers, which by this Constitution are vested in the King."

When His Majesty King Kamehameha V (pictured right) ascended to the throne, he had refused to take the oath of office until the Constitution was altered. This refusal was constitutionally authorized by Article 94 of the 1852 Constitution which provided that ". [t]he King, after approving this Constitution, shall take the following oath. "

This provision implied a choice to take or not take the oath, which His Majesty King Kamehameha V felt should be constitutionally altered. Another provision of the 1852 Constitution needing alteration was the sovereign prerogative provided in article 45 which stated that ". [a]ll important business of the Kingdom which the King chooses to transact in person, he may do, but not without the approbation of the Kuhina Nui (Premier). The King and Kuhina Nui (Premier) shall have a negative on each other's public acts."

This sovereign prerogative allowed the Monarch the constitutional authority to alter or amend laws without Legislative approval. These anomalous provisions needed to be altered along with the instituting of voter qualifications for the House of Representatives. His Majesty King Kamehameha V, in Privy Council, resolved to look into the legal means of convening the first Constitutional Convention.

On July 7, 1864, a Convention was called for by His Majesty King Kamehameha V in order to draft a new constitution. The Convention was not comprised of delegates elected by the people with the specific task of altering the constitution, but rather their elected officials serving in the House of Representatives, together with the House of Nobles and the King in Privy Council who would convene in special session. Between July 7 and August 8, 1864, each article in the proposed Constitution was read and discussed until they arrived at Article 62. Article 62 defined the qualification of voters for the House of Representatives. After days of debate over this article, the Convention arrived at an absolute deadlock. The House of Representatives was not able to agree on this article. As a result, His Majesty King Kamehameha V, in exercising his sovereign prerogative by virtue of Article 45 of the constitution, dissolved the convention and proclaimed a new constitution on August 20, 1864.

In His Majesty King Kamehameha V's speech at the opening of the Legislative Assembly of 1864, he explained his abovementioned action of dissolving the Convention and proclaiming a new constitution. He stated that the ". forty-fifth article (of the Constitution of 1852) reserved to the Sovereign the right to conduct personally, in cooperation with the Kuhina Nui (Premier), but without the intervention of a Ministry or the approval of the Legislature, such portions of the public business as he might choose to undertake. "

This public speech before the Legislative Assembly occurred without contest, and therefore must be construed as a positive statement of the approbation of the Kuhina Nui (Premier) as required by Article 45 of the said Constitution of 1852. However, this sovereign prerogative was removed from the 1864 Constitution, thereby preventing any future Monarch of the right to alter the constitution without the approval of two-thirds of all members of the Legislative Assembly. All articles of the constitution previously agreed upon in convention remained, except for the voter requirements for the House of Representatives. The property qualifications instituted in Articles 61 and 62 were repealed by the Legislature in 1874.

Contrary to recent historical scholars, the 1864 Constitution did not increase the authority of the Monarch, but rather limited the power of the Monarch formally held under the 1852 Constitution. Under what has been termed the Kamehameha Constitution (1864), the Monarch was now required to take the oath of office and the sovereign prerogative was removed. Also removed was the office of the Kuhina Nui (Premier), which was found to be overlapping with the duties of the Minister of Interior. The bi-cameral nature of the legislative body was also removed. Where once the legislature would formally sit in two distinct Houses (House of Nobles and the House of Representatives), it now was changed to a uni-cameral House where the ". [l]egislative power of the Three Estates of this Kingdom is vested in the King, and the Legislative Assembly; which Assembly shall consist of the Nobles appointed by the King, and of the Representatives of the People, sitting together."

On December 11, 1872, His Majesty King Kamehameha V passed away without naming a successor to the office of Constitutional Monarch. As a consequence to the passing of the late King, the Legislative Assembly readied itself to exercise the constitutional authority it possessed to elect, by ballot, a native Chief to be the Constitutional Monarch. Article 22 of the Constitution of 1864 of the Hawaiian Kingdom provides such authority and states "..should the Throne become vacant, then the Cabinet Council, immediately after the occurring of such vacancy, shall cause a meeting of the Legislative Assembly, who shall elect by ballot some native Ali'i (Chief) of the Kingdom as Successor to the Throne. ".

On January 8, 1873, William Charles Lunalilo was elected as successor to the office of Constitutional Monarch in accordance with Article 22 of the Constitution of 1864. One year later on February 3rd, 1874, His Majesty King Lunalilo (pictured right) died without naming a successor. The Hawaiian Legislature once again met in special session and elected David Kalakaua to the office of Constitutional Monarch on February 12th, 1874. In accordance with the Constitution, His Majesty's first royal act was to nominate and confirm his younger brother, William P. Leleiohoku, as successor.

On April 10, 1877, following the death of heir-apparent William P. Leleiohoku, King David Kalakaua (pictured left) publicly proclaimed Lydia Kamaka'eha Dominis to be his successor to the office of Constitutional Monarch in accordance with Article 22 of the Constitution of 1864.

In 1880, the Legislative Assembly passed an Act to Provide for the Codification and revision of the Laws of the Kingdom. His Majesty's Ministers requested an opinion of the Justices of the Supreme Court, in regard to the 1880 Act, to determine what needed to be done. The Justices stated there was no need to establish another code, but rather a compilation be made of the laws, then in force, and as they stood amended, but without any changes in the words and phrases of statutes. Pursuant to the opinion of the Justices and in accordance with the 1880 Act, a book was published in 1884 entitled the "Compiled Laws of the Hawaiian Kingdom."

On October 16, 1886, the Hawaiian Legislature was adjourned by King David Kalakaua after it met in Legislative session for 129 days. This Legislature was not scheduled to reconvene in Legislative Session until April of 1888. Article 46 of the Constitution of 1864 provides that the ". Legislative Body shall assemble biennially, in the month of April, and at such other time as the King may judge necessary, for the purpose of seeking the welfare of the nation."

The Bayonet Constitution of 1887.

In 1887, while the Legislature remained out of session, a minority of subjects of the Hawaiian Kingdom and foreign nationals, which included citizens of the United States, met in a mass meeting to organize a takeover of the political rights of the native population in the Kingdom. These individuals were organized under the name "Honolulu Rifles." On July 1, 1887, these individuals threatened His Majesty King David Kalakaua with bodily harm if he did not accept a new Cabinet Council. On July 7, 1887, a new constitution was forced upon the King by the members of this new cabinet. This new constitution did not obtain the consent nor ratification of the Legislative Assembly who had remained adjourned since October 16, 1886.

Under this so-called constitution deriving itself from the Executive branch and not the Legislative branch, a new Legislature was elected while the lawful Legislature remained out of session. The voters, which for the first time included aliens, had to swear an oath to support the so-called constitution before they could vote. The insurgents used the alien vote to offset the majority vote of the aboriginal Hawaiian population, in order to gain control of the Legislative Assembly, while the so-called 1887 constitution provided the self imposed Cabinet Council to control the Monarch. This new Legislature was not properly constituted under the Constitution of 1864, nor the lawfully executed Session Laws of the Legislative Assembly of the Hawaiian Kingdom.

In spite of the illegal efforts to promulgate this so-called constitution, the 1886 Legislative Assembly did not ratify this so-called constitution pursuant to Article 80 of the 1864 Constitution. Article 80 states "Any amendment or amendments to this Constitution may be proposed in the Legislative Assembly, and if the same shall be agreed to by a majority of the members thereof, such proposed amendment or amendments shall be entered on its journal, with the yeas and nays taken thereon, and referred to the next Legislature; which proposed amendment or the next election of Representatives; and if in the next Legislature such proposed amendment or amendments shall be agreed to by two-thirds of all members of the Legislative Assembly, and be approved by the King, such amendment or amendments shall become part of the Constitution of this country."

Organized resistance by the native subjects of the country resulted in the creation of the Hawaiian Political Party, also known as the Hui Kalai'aina, who protested against the so-called constitution of 1887. Hui Kalai'aina consistently petitioned His Majesty King David Kalakaua to resort back to the 1864 constitution because it was the legal constitution of the Country.

Notwithstanding the extortion of the so-called constitution of 1887, commonly known as the "bayonet constitution," the Constitution of 1864 and the Session laws of the Legislative Assembly enacted since October 16, 1886, still remain in full force and have legal effect in the Hawaiian Kingdom until today. Article 78, of the Constitution of 1864, provides that all ". laws now in force in this Kingdom, shall continue and remain in full effect, until altered or repealed by the Legislature; such parts only excepted as are repugnant to this Constitution. All laws heretofore enacted, or that may hereafter be enacted, which are contrary to this Constitution, shall be null and void."

On January 20, 1891, His Majesty King David Kalakaua passed away in San Francisco, while visiting the United States. His named successor, Lydia Kamaka'eha Dominis, ascended to the office of Constitutional Monarch and was thereafter called Queen Lili'uokalani (pictured left). On January 14, 1893, in an attempt to counter the effects of the so-called constitution of 1887, Her Majesty Queen Lili'uokalani, drafted a new constitution that embodied the principles and wording of the Constitution of 1864. This draft constitution was not Kingdom law, but remained subject to ratification by two-thirds of all members of the legitimate Legislative Assembly, that had been out of session since October 16, 1886.

The revolutionaries who actively participated in the extortion of the so-called 1887 constitution were also the same perpetrators affiliated with the unsuccessful revolution of January 17, 1893. Between 1887 and 1893, the self imposed government officials who were installed under the so-called 1887 constitution became an oligarchy, as they tried to combat the organized resistance within the Kingdom.

Read about Hawaii's post-1893 history under U.S. Occupation.